Current position: 89° 54′ N, 38° 32′ O

It’s not exactly like cutting butter!

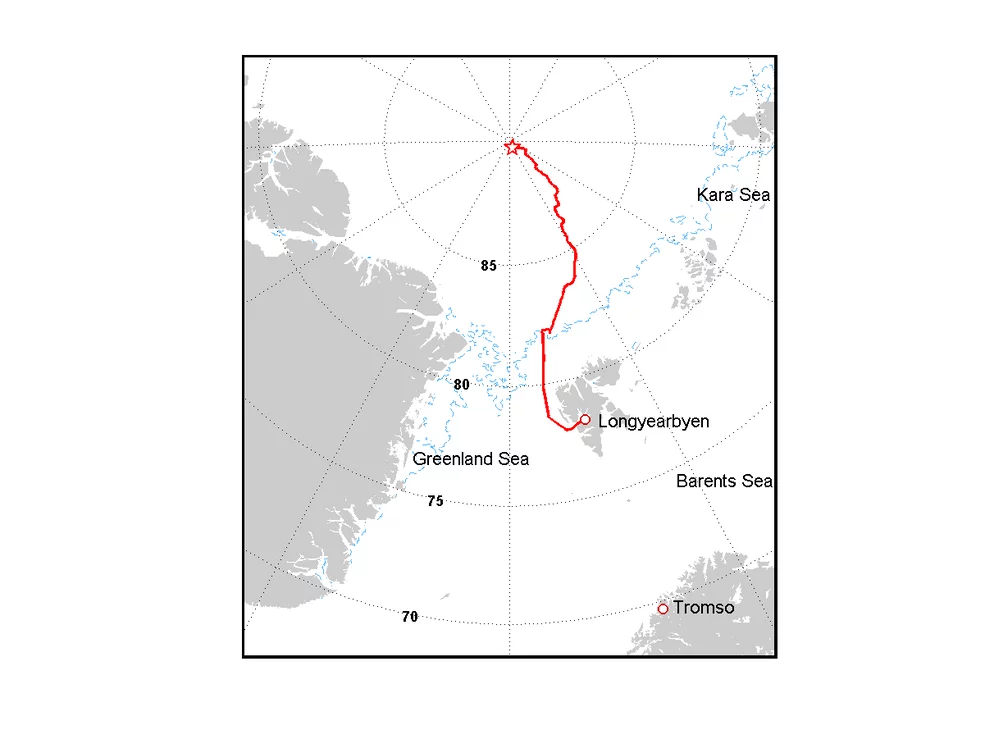

It’s not exactly like cutting butter, the journey towards the North Pole. Since leaving the marginal ice zone late on 3 August, we have moved steadily further north in search of a “perfect” ice floe that will accommodate the needs of all projects on board. Satellite images indicated large floes and of about a meter thickness, that’s more than enough to land a helicopter, in the North Pole vicinity. So off we went, heading north. And after 9 days we reached the furthest north: 89°54′ N. That’s worth a celebration and group picture. The stairs were let down to the ice and the majority of the expedition team set foot for the first time on Arctic pack ice. What a moment! “Secretly”, but definitely adding to the aerosol group’s good mood, ions started to appear in the atmosphere, messengers of the early stages of a new particle formation event…

Admittedly, it took longer than expected to get to this geographical point. On the way there, we encountered a variety of ice conditions: First the passage was relatively easy when water channels were present amongst the floes. Then the first year ice became denser and the icebreaker started working harder, still making a decent 5 knots, roughly 9 km/h. We could see plenty of dark melt ponds and many open leads. A couple days later, the winds finally put Oden to a test. The steady easterly wind had pushed the ice towards our track, making it a very dense pack, up to two meters thick, and with ridges. Moving north happened at a much slower pace then, roughly 3 knots. Standing on the main deck looking down, we observed huge pieces of ice popping up next to Oden. Some completely white, some bluish, some greenish and some full of algae. It’s not only a visual spectacle; it’s also extremely noisy and bumpy. The pack ice was then so dense that we could not see any open water and some of the melt ponds appeared to become bluer. That’s a sign for multiyear ice. Oden now really had to work hard. She moves forward by pushing herself on top of the ice a couple of meters and then her weight crushes the pack that then reappears on her sides where we stand watching. In tough ice conditions, the officer on watch had to back up the ship and take several attempts. In such conditions, the helicopter is sent out to do a recon flight to scout for the most convenient path. That worked for a day. Then heavy fog settled in for 24 hours and we had to stand still. For the online aerosol team this was an excellent opportunity to put all the instruments and inlets to a test in conditions similar to what we hope to encounter at the five week long stations. We collected the first data of activated and interstitial aerosol during fog in this expedition. Supersaturations were very low and preliminary data suggests that organic aerosol is depleted in the activated particles.

As soon as the fog lifted, the heli went scouting and found the track of the Russian nuclear icebreaker 50 Let Pobedy that apparently had visited the North Pole a couple of days before us. Following their path, we advanced North. The ice pack actually opened up again, allowing Oden to travel in water channels. Then heavy ice followed and we had to stop again. That was at 89°54′ N, about 9.6 km from the North Pole. Ice conditions were too tricky to keep advancing, so the expedition leadership decided to have the North Pole celebration on the spot. It is internationally agree that within 25 km of the Pole, one may celebrate. Of course, scouting for the “perfect” ice floe had continued throughout the past days and the preferred location seems to be close by now. It is a matter of finding a time window of good visibility to make a decision. In the meantime, the ship is on standby and we continue our measurements.